What Users Ask for Isn't Necessarily What They Want

UX practitioners are problem solvers, and it’s our job to not merely take customer requests at face value. Instead, use these techniques to uncover and solve the real problem at the root of the request.

This post is going to be a little shorter than last week's, and this week is AI-free. If you haven't subscribed yet, please take a sec to click that there button down there and sign up. 👇 It's free, I won't spam you, and of course you can unsubscribe at any time.

And if you're enjoying the content please recommend Design Flaw to your friends and colleagues.

OK, so enough with the formalities, let's get to it.

This week I caught an article on how to design for current customers without alienating future ones. It’s a great article with some nice solutions to working around seemingly inflexible requirements from customers. Product managers and sales teams tend to take the demands of major customers at face value, which seems like a good idea but can have some repercussions later on.

I’ve seen the results of this myself, and you probably have too. Products become bloated and complex as teams add one-off features for specific customers. Over the years, some of those features may become disused, especially if the requesting customer ends up leaving anyway. As people come and go we may forget why a certain feature was even added or who uses it. But it’s very hard to remove those features because someone might be using it.

So you wind up with a product full of indelible features that are custom-tailored to one specific use case.

This is a big problem, and it got me thinking about the root cause, which is this: people often ask for the wrong thing.

I know what you’re thinking: “UX practitioners are supposed to be empathetic toward what users want, so it seems antithetical to tell users that they are wrong.”

I’m not saying that users are wrong, but they do often look at things from their own limited perspective. I wrote about this on the 58 Creative blog awhile back, but will share the gist of that article here.

When I worked at the Texas Education Agency (TEA) I had a colleague ask if we could build a feature to import her program data from a spreadsheet so that she could quickly enter data from school districts.

That seemed like a simple enough solution, except that we had just spent three years and a few million taxpayer dollars eliminating uploads like these. In most cases the new system provided ways for the school district employees to enter their own data. This was much more efficient than having them collect data into a spreadsheet and email or fax it to TEA, where a program manager would reformat the data and send to someone else for processing.

So if the district staff could enter their own data, why would they need to send an update manually? Turns out that every now and then someone missed a deadline or a there was a last-minute change after the data entry window was closed.

If we frame this as a user story, we get this:

This highlights the goal: so that I can update school district data.

From there, we can flip it into a How Might We (HMW) question:

After gathering some additional details I suggested that we add an edit function to the screen used to review district-submitted data. This was faster, simpler, and didn't open any gaps in the audit process.

So why did my colleague ask for the spreadsheet import? Because that's what she had done for years and was most familiar with. To her, it was the obvious solution, even if not the best.

Designers are problem solvers, so when discussing new features we need to do our best to understand the underlying problem instead of just taking the request at face value. This is why research, even if done informally, is so important to UX design.

Getting to the Root Cause

Conducting formal UX research is a great way to gain a deep understanding of the problem. But some teams may not have access to a researcher, deadlines may not allow for a full research process, or the problem may not warrant a full-blown research process.

Fortunately, we have plenty of tools that we can use to quickly gain a better understanding. I've already mentioned using user stories and HMWs to reframe the request, but here are a few more easy-to-use but effective techniques to gain understanding.

Five Whys

I love the 5 Whys process, because it really is as simple as asking “why” a bunch of times. You can run a formal 5 Whys workshop with group of users, but it’s also quite effective in one-on-one situations. If you’re in a situation where users are asking for something specific that doesn’t seem to make sense from an overall product or design perspective then just start asking why. Just do so in a curious, respectful manner; you don’t want to come off sounding like a jerk.

This is the technique I used in the TEA example.

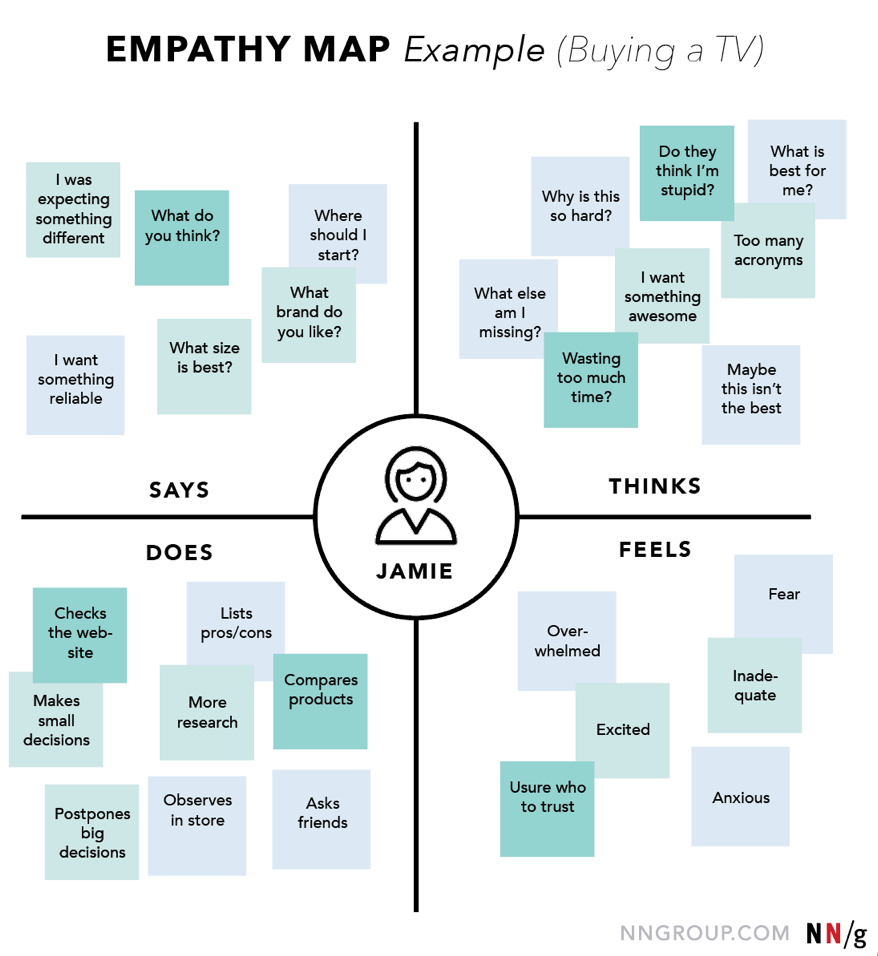

Empathy Mapping

If you have a little more time, empathy mapping is another great tool. Empathy maps rely on user interviews to uncover what users say, think, do, and feel. It’s fairly common to find gaps or conflicts among these quadrants. Users may say one thing but actually do something else. These juxtapositions are important to understanding the actual problem that needs solving.

Field Studies

If you have direct access to your users then field studies can be incredibly effective at uncovering pain points. In a field study, you directly observe users performing their tasks. You can do this by sitting at their desk with them or even via a screen share session. Conduct these much like you would a moderated usability test: have the user talk through their process as they do it. This way, you can understand what they do, how they do it, and why.

I once conducted a field study in a call center for a major bank. We were redesigning an interface for call center agents to use when processing credit card payments. During the field study we learned that most agents kept a text document of commonly-used notes and codes open on their desktops so that they could quickly copy-paste during or after a customer call. This had never come up in hours of interviews and meetings with the product teams, but was hugely important to the folks using the product. It opened the way for us to add an important prodcut feature for the call center users.

Field studies are another way of finding differences between what people say and what they do – and can also inform your empathy mapping process.

Summary

When considering new features or product updates it’s important that we look below the surface to understand the real problem that needs to be solved. Users know what needs to be done, but their own experience and perspectives may cause them to request something that makes sense to them despite not being the best way to address the issue.

We have a variety of tools to help, even with minimal time and resources. So be curious, ask the right questions, and build great products! Your users (and sales) will thank you.

Beautiful Ice Fishing Huts

I don't personally find the concept of walking onto a frozen lake and sitting on the ice for hours to be particularly appealing. But plenty of folks do, and good for them! Whatever your opinion on ice fishing, no one can deny that Richard Johnson took some really beautiful photos - you can check out the collection on his website and can even pick up a print if you'd like.

Japanese Government Finally Abandons Floppy Disks

Yes, you read that right; in January 2024 Taro Kono, Japan's minister for Digital Transformation, finally won his "war on floppy disks." Before last month, the Japanese government required many business submissions be made on floppies, CD-ROMs, or other archaic storage media.

But that doesn't mean the end of floppies; to the contrary, they are still widely used for all kinds of mission-critical use cases. In fact, the US nuclear weapons systems relied on 8-inch floppy disks all the way up to 2019. News you can use, indeed.

Stop Neglecting Your Internal Products

Earlier this week I wrote about the propensity for product managers to neglect their internal products. While it makes sense that companies want to focus their efforts on customer-facing (i.e., money-making) products, there are plenty of good reasons to put some effort into your in-house products. Subscribers can read all about it right here.